Self-Sovereign Identities: It Is Going To Happen!

The term ‘Self-Sovereign Identity’ (SSId) has been attracting quite some attention in the (relatively small) world of ‘Internet-and-Identity’, with initiatives such as Sovrin and uPort as examples (and, of course, the Self-Sovereign Identity Framework (SSIF) that has been kicked-off in the synonymous project of the Techruption consortium). The basic drivers for these initiatives are privacy (we want to control our own data) and business benefits (just for the Netherlands, cost savings alone are estimated to exceed 1 Billion euro’s). Here is what it is all about.

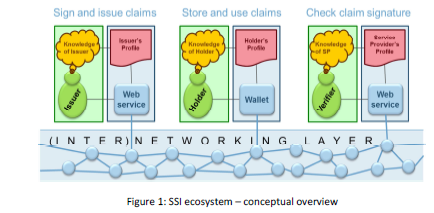

Bitsonblocks.net says: “Self-sovereign identity is the concept that people and businesses can store their own identity data on their own devices, and provide it efficiently to those who need to validate it, without relying on a central repository of identity data. It’s a digital way of doing what we do today with bits of paper ”. The high-level idea is that you get an app on your mobile phone. This app is commonly called a ‘wallet’, because it holds claims about you – the holder, and such claims are

todays currency and that of tomorrow. You collect such claims from issuers, i.e. parties such as banks, governments or even supermarkets, that create and sign claims that they know to be true, and subsequently issue them to you for storage in your wallet. You can also issue your own claims, or have friends issue claims to you.

When you visit a SSId-ready website in which you have to fill in forms, you – as the Holder of a wallet – can let the wallet fill in the parts of the form for which it has claims. This is not only the usual data, such as your name, address etc. This can also be attestations, e.g. by your physician (e.g. for a diagnosis), bank (e.g. for your debt, or monthly income), etc. Thus, you no longer have to retype the usual data over and over again, and you also don’t need to visit your physician or bank to obtain written attestations Businesses also profit: they can have users not only provide the necessary information, but also provide attestations that are issued by parties that they actually trust. This relieves them from having to validate this data themselves: all they have to do now is check the digital signature.

This is a big deal. Banks, insurers, government agencies, educational institutions, health workers – the list is endless – all spend so much time and effort to validate information that is provided to them, and repairing situations in which they ended up because they made an error in that validation. Only for the Netherlands, with its 7M households, this would add up to an estimated 1 billion Euro’s every year1. Even if this number is one order of magnitude off, the business case is quite clear.

Issuers whose attestations provide a major contribution to such savings may develop new business models, in which they can be rewarded for having made such contributions.

However, we’re not there yet. Reaping such benefits requires the cooperation of many and diverse organizations, that must provide and/or consume attestations from one another. The benefits increase when attestations can be used cross-domain: health organizations for example will need attestations from financial organizations (banks, insurers), governments, the converse is true as well.

We expect another increase when attestations can be used inter-nationally. We still need to find out what the best way is to get organizations to cooperate in this manner, what they will need from one another to do so, and how this can be supported and made easy. We strive towards an Identity layer for the Internet, which is long wished for. In the end, solutions should work for individuals, SME’s, large corporations, governments; in short: for anyone anywhere.

We envisage it to be sufficiently free, open, standardized and easy to use, not hampered by e.g. intellectual property claims that make it prohibitively costly to use the technology. That is not to say that no money can be made. We will see wallet-vendors compete with one another, and software being created to help issuers and verifiers (i.e. web services that verify and then consume the claims) get the most out of it. The line between what should be standardized and open, and what should be

left to the market, is not very clear yet, and is currently being investigated.

Much of the technology that already exists or is currently being fleshed out, is open source. An example of existing software is IRMA (by the Privacy by Design Foundation). Other initiatives such as DIF and Hyperledger Indy, are open source. Relevant standards that are being developed, e.g. on distributed identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Claims, will be free.

Having the technology isn’t going to cut it though. The IRMA technology has been around for many years, but has only been adopted at a very small scale. It has been made really easy to install and test the app, and integration of the (open source) verification software with existing web services has been made quite easy (a simple JavaScript call suffices for testing, full adoption requires the installation and configuration of an additional server), there is (currently) hardly any connection to the business level. However, at that level the (business) risk of using it is assessed, and decisions forallocating budget and effort to implement it are being made.

Then, in order to take full advantage of the technology, businesses may have to (partially) redesign their processes, in order to find out what kinds of attestations are required, which issuers to trust, and what the risks are of attestations that are properly signed, yet untrue2. This is a new topic for businesses, one that they have to be introduced to and acquaint themselves with. Explicitly addressing this issue may help to reduce the risk that organizations perceive as they ponder on

whether or not to adopt this technology.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which will become effective in May 25th of this year, may also turn out to be an effective enabler for adopting SSI. After all, the GDPR requires businesses to review their processes so as to determine what kinds of (personal) information they use, and for what purpose it is used. They need to be capable to inform the user (in terms that (s)he can understand) about the information they have about the user and its purposes. They have to implement or update their processes to facilitate the rights of individuals, such as the right to correct

information, and the right to be forgotten. Many organizations will not meet that deadline.

Integrating the requirements of the GDPR in the protocols for self-sovereign identity will not only help organizations with the validation of information that they get from users, but can also help them to provide the (privacy-related) information to users as the GDPR requires.

Self-Sovereign Identity: it is going to happen. The business benefits are big enough. The ‘fire’ of selfsovereign identity is burning across the globe, and is increasing its ‘heat’. There seems to be sufficient consensus on the underlying principles (albeit that they also need to be worded in a better way). I am thrilled to be part of the SSI-group within TNO that contributes to these developments.

1 It seems quite reasonable to assume that the number of forms multiplied by the processing cost is in the order of 150 euro per household per year. Then, the cost for fixing errors has to be added to that.

2 One reason might be that the issuer is mistaken or led to believe false statements are in fact true. Issuers may also intentionally sign false statements, e.g. to enable the illegitimate use of services that require them. Finally, false statements that are signed with the signing key of a (well-intentioned) issuer may also appear when an unauthorized person seized an opportunity to use that key in an insufficiently secure environment.

Rieks Joosten

02 March 2018